I

n an interview with the Eric Metaxas Radio Show, author Myron Magnet explains how Jim Crow laws in the South spurred a young Clarence Thomas’ interest in judicial overreach. Those laws sprang from Supreme Court decisions in the 1870s that violated the meaning and purpose behind the 13th and 14th Amendments and left newly freed slaves open to abuse by state and local governments.

The Jim Crow laws that resulted from this overreach eventually spread to Savannah, Georgia, where Thomas grew up. “This is personal to [Thomas],” Magnet explains. “[He] couldn’t drink from this water fountain or walk across that park or use that certain library.” When he arrived at the Supreme Court, Thomas sought to overturn the legal precedents that had resulted from the 1870s decisions.

His effort directly recalled the spirit of the Constitution’s original framers. “If we really are endowed with these rights, and if our Constitution was established to protect these rights,” says Magnet, “let’s hang on to it. Because nobody ever had a more up-to-date idea than leaving the citizen free to pursue his own happiness.” Thomas worked to preserve that idea, having first been inspired by the injustice of Jim Crow in his own life.

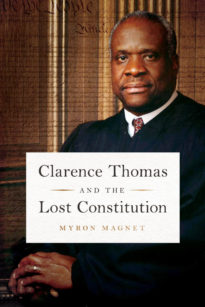

Learn more about Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution in the interview below: