J

udge J. Harvie Wilkinson III sat down with ChangeUp Media’s Ben Weingarten to discuss his new book All Falling Faiths: Reflections on the Promise and Failure of the 1960s. What follows is a full transcript of their discussion, slightly modified for clarity.

You can also listen to their interview in its entirety below. And to automatically receive Encounter Books Podcast interviews like these, be sure to subscribe to our podcast in the iTunes store.

Ben Weingarten: Judge, your book is part memoir and part political and social commentary. At its most pessimistic parts, I would say it reads like an elegy for America. But at the same time, you find optimism in the spirit of the 1960s, and clearly hope that we can rekindle some of that optimism, but infuse it with the virtues of the past. What compelled you to write this book at this time?

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III: Well, I early got the idea that it would be a pure memoir. I started on it just by collecting fragmentary notes over, really, almost 50 years. I wanted to do that because I knew so little of my grandparents, and nothing at all of my great-grandparents. And I felt this emptiness about it. And I thought, “Well, I don’t want my grandchildren and great-grandchildren to know nothing about their ancestors, who really put us on this Earth.” So, that’s how it all got started, is that kind of a memoir. But then, as I started collecting it and reconstructing the memoir and trying to make some sense of it, I realized it couldn’t just be a memoir — that I couldn’t discuss the 1960s and the 1950s without discussing their impact upon the present day.

I thought I’d left the 1960s behind for good. And these last two or three years, it’s as though they’ve come rushing back.

And particularly…I mean, when I left the 1960s, I thought they were in the rearview mirror. I thought I’d left them behind for good. And these last two or three years, it’s as though they’ve come rushing back. It’s like they were only in remission. So much of what I have seen has been a bit of a flashback, and a replay of that very tumultuous decade. And so, what I really wanted to do is to say, “Look, this is what it was like to go through the 1960s. And in many ways, it was not at all a good experience.” And so I wanted to talk with people who had been through it along with me, and see if their impressions coincided with my own. And I wanted to implore upcoming generations to learn from our experience, not to go through this again because the ’60s deprived us of so many values and diminished so many institutions and introduced so much rancor. And there’s only so much of this recurring rancor that even a great country like ours can sustain.

Ben Weingarten: One of the areas where we’ve seen probably the most tumult, and it seemingly is just a self-perpetuating vicious cycle, is in the first section that your book focuses on, which is education. And I think that’s not coincidental at all, given the importance of ideas in the direction of a society. And in particular, you talk about your experience as an undergraduate at Yale University, where you graduated in 1967, which I think is a good proxy for the American education system more broadly. It sort of set the standard, set the direction that we’ve seen over the last 50 years. And if I were to distill it, I would say that you describe a campus where emotion trumped reason, and all of the classical liberal ideas of the past were turned on their heads. What made the education of the ’60s a toxic inflection point in US history?

The '60s deprived us of so many values and diminished so many institutions and introduced so much rancor.

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III: Well, part of it was simply the spirit of intolerance that took hold, and the really sometimes violent means by which the intolerance was carried out. And so the techniques of intimidation in higher education were pioneered in the 1960s: People grabbing speakers’ microphones and shouting them down and not listening, and sitting-in in administration buildings and closing classes. And so you had this rising tide of intolerance, which is so contrary to the spirit of free speech and the First Amendment. And that’s continued on to the present day, where people try their best to dis-invite graduation speakers, and to shout down views they don’t agree with.

But there was a broader problem, apart from the sheer lack of tolerance, which was bad enough. The broader problem was this intense negativity that was introduced by the 1960s toward this wonderful country of ours. And it took place on several fronts. Number one: That American History was spun into a narrative of solely oppression. And gosh knows, we’ve made our mistakes, and such things as slavery and segregation are shameful chapters in our history. But there’s also so much good about what this country stands for in its history, and this Constitution that we have. And we have lit the beacon of freedom throughout the world; we pioneered the Bill of Rights; we worked with a democratic system which gives people say over their own destiny; we’ve had a system of capitalism that’s brought great general prosperity to our country and, to a greater extent, to the world.

And during the 1960s, the good side of the American story was neglected, and it just became one long thing about how we had oppressed, which had a germ of truth, but which was totally unbalanced. It didn’t say the good things for which America stood, and for which I believe it continues to stand. And the other thing, the other negativity about the 1960s, had to do with the private sector. In so many of my classes, government was exalted because it reined in the private sector, and it was like “The private sector could only do bad,” that all it was, was predatory.

During the 1960s, the good side of the American story was neglected.

And [the argument was put forth] that these captains of industry ground down employees and polluted the land and everything. The private sector has its problems, and some degree of regulation is necessary to curb its excesses, but it’s also been a wonderful engine of job creation and of inventiveness. And it’s brought consumers an extraordinary array of goods and…I grew up in a family of bankers, and I saw the way it operated, and those banks made a lot of things possible for a lot of people. And so, when I got into these classes at Yale, they were just running the private sector down. Now, if you run down American history, and you run down the private sector and you find nothing but things to complain about, that’s not good. You have to have balance, and that’s what was lacking. It was just all so negative about America, and that eventually just saps a nation’s morale.

Ben Weingarten: And what’s so ironic about it is that, you talk about in the book sort of a nihilism, a pervasive nihilism. And also, of course, a moral relativism that existed in the ’60s and continues to this day, which would say that there is no such thing as good and evil, yet labels all of those fundamental American institutions evil. And so then you have to question, what is “the good” for people who are moral relativists and say there should be no black or white, good or bad.

I don’t think we can ever come together as a country and repair the damage that the 1960s did to us unless we become a nation of listeners, and speak in a little softer tones.

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III: Well, that was another problem is that on the one hand, there were these judgments that were thrown up, and America was painted in these dark tones; and on the other hand, everything was sort of relative, and we lost many of the values that were sort of the stars that guided us. We lost a sense, I think, of proper comportment and in relations between the sexes, the family unit was weakened to some extent, religious faith was weakened to some extent, our capacity for national unity was impaired. So, it was these sorts of values for which… They weren’t perfect, and nobody can live by these aspirational values every day of the week, but they were good values. And they anchored us. And they gave us a sense of orientation, and constancy and something really to live for and guide our lives for. And those were just undermined. So, your questions point up the fact that there’s so much cumulative damage that was done by that decade, but I didn’t wanna just shout at people about this kind of thing. I want to talk to them, and go hand in hand with them and try to persuade.

And so I felt I could do that with a memoir, which was as personal and as intimate as I could make it, and said, “Look, this is how it was to live through those days, and I hope you’ll take this journey with me. I’m not rushing to the barricades. I’m not gonna shout. I just want you to sit down with me or walk with me.” And I just wanted to make it personal, because it’s such a volatile subject, and you can’t bring it up at a dinner party without sending everybody into a spiral. And so I said, “I don’t wanna do that.” I just wanna make it a personal journey. And I want the reader to come along with me, and at the end of the day I would hope that we could all see both sides of the ’60s argument. And it may be some people that feel that the ’60s was the greatest thing ever, might at least listen to my views, that I think it inflicted incalculable damage upon this society. But I’m up for listening too, ’cause I don’t think we can ever come together as a country and repair the damage that the 1960s did to us unless we become a nation of listeners, and speak in a little softer tones. So that’s why I settled on the memoir form.

Many of us have seen the flaws in America, but does that mean we abandon America as our home?

Ben Weingarten: Judge, you took up the law at a time when, as you describe it, America witnessed “lawlessness writ large.” Speak a little bit about your legal education, and also your run for Congress [the U.S. House of Representatives], which was a very interesting little vignette in and of itself. Speak a little bit about that episode in your life, and the broader ramifications that you took from it.

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III: Well, I thought people ought to be engaged in activism in a good way. People were so often, rather than all this shouting and trying to vilify the country and everything, my thought was, “Well, what I wanna do is get involved in the democratic process and try to persuade folks that even with this youthful generation that they were so worried about that we could make a constructive contribution by working within the system.” And I thought a good way for me to proceed was to try to run for Congress. I was only 25 years old, and…I barely met the age limit, but I won the Republican nomination, and then faced a three-term Democratic incumbent.

It was tough sledding back then to be a Republican in the South, so my opponent had this, really a tag line, which he put on all his billboards and his ads, and it said, “Send Satterfield back to Congress, and Wilkinson back to school” because I was a young guy, and I looked young. I had taken a sabbatical from law school to run for Congress, and everybody, even the consultants to my campaign, were so worried about me being so young, they didn’t wanna use a picture. They wanted to use an etching for me. And then they wanted to surround me completely by senior citizens, to indicate that I wasn’t some sort of radical, and I wasn’t up to overthrow anybody.

I lost about two-to-one, or maybe it was even three-to-one, I don’t know, but it wasn’t close. But am I glad I did it? Absolutely, because to my way of thinking, this was a really diversified and pluralistic country, and the best way for me to learn about people outside my own little sphere was to go run for public office, and talk to people on the street, and at their offices, and do handshaking tours, and listen to what they had to say, and go into ethnic communities and into the African-American community and try to get a sense of what the country was.

We lost a sense, I think, of proper comportment and in relations between the sexes, the family unit was weakened to some extent, religious faith was weakened to some extent, our capacity for national unity was impaired.

Ben Weingarten: Now, one of the things that you talk about at length in the book is the perversion of undergraduate education, and we’ve seen that there are all manner of dubious legal theories that have been developed in the time since the ’60s as well, probably just subsequent to your time in law school. Do you see a parallel trajectory there? And also, having served in the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, and seeing where it is today, does that in some sense affirm your worst fears about what has become of the law?

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III: I became very concerned about what had happened to the law during the 1960s in several ways. One was simply that there were these really terrible riots that took place, particularly in the summer of 1964 and 1965 in Harlem, and Detroit, and Watts and Rochester. And then there were these terrible assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy, and of Martin Luther King. And those just shook us enormously. It’s hard to imagine how traumatic it was to see these very inspiring figures just shot dead. The effect on us was just incalculable.

Then on the other side, you have these riots that unfortunately visited, just really deprived shopkeepers of their stores and harmed passing motorists and threw rocks at police.

But on the other hand, you had whole police departments careening out of control. That happened in Birmingham, and it happened in Chicago at the 1968 Democratic Convention, and it happened in Stonewall and it happened at Kent State.

People in the 1960s, they felt if they thought something was right, that they were justified in taking the law into their own hands.

And so you had the law that was just assaulted from both sides, from the people that were supposed to obey it and the people that were charged with enforcing it. Something of that is taking place today. I was so concerned and disappointed about the riots in Ferguson and in Baltimore, and I was so upset about some police actions that were simply not justified. This is not the way to go. Violence is never the way to go. Those great strides in the ’60s were made peacefully with the march on Washington in 1963, and the march from Selma to Montgomery. As the decade went on, this violence supplanted it. It’s a great concern of mine that we’re seeing a lot of the same things. People in the 1960s, they felt if they thought something was right, that they were justified in taking the law into their own hands.

That’s proved a contagious principle around the globe. You saw it in 9/11, and its long aftermath, that if I have a particular vision of an ideal society, and if I think I’m right, then I can go to all sorts of lengths in harming other people. That’s a pernicious notion, and it’s what the 1960s set in motion.

All that’s bad around us should never extinguish hope for what can be good.

All of this lawlessness and the idea of taking law into their own hands has become even more dangerous today than in the decade that gave it birth, because the advent of social media has provided an amplification for those who have been on violence. Social media is good in so many ways, but it can amplify violent acts. And the means of carrying out violence have become so much more lethal.

And so you have these ’60s theories about law, which is that we don’t have to obey it if we don’t agree with it. That just undercuts the rule of law completely, because it’s a social compact. And law really means nothing if we only have to obey those things that we find agreeable. But given the increase in the lethal nature of weaponry and terrorism, and given the way that the media amplifies some of the lawlessness that takes place, we are faced with the trend that the 1960s helped to set in motion. I think it has become so much worse.

Ben Weingarten: Judge Wilkinson, you grew up in the South at a time when the South was segregated, but there were still these sort of romantic traditional values and principles of chivalry and duty and family and the like. And then you went up to Yale and before that Lawrenceville, a prep school in New Jersey, and you talk about the loss of home. Speak a little bit about to how the loss of home fits into your overall thesis.

And so you have these '60s theories about law, which is that we don't have to obey it if we don't agree with it. That just undercuts the rule of law completely, because it's a social compact. And law really means nothing if we only have to obey those things that we find agreeable.

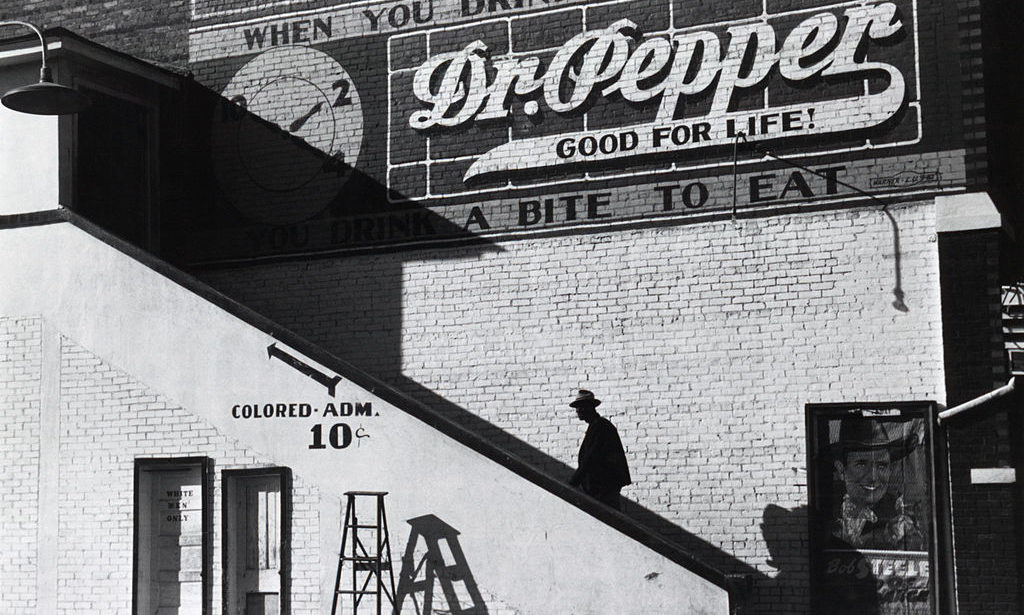

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III: Well, when I went North, I recognized that there were — along with the good in which I grew up — that there were so many wrong things about the segregated South, and I began to see them; just the things in daily life that were wounding and dehumanizing to African-Americans, and it must have hurt them a very great deal. In my boyhood there wasn’t a lot of coarse language, thankfully, but there were just little daily customs that must have just cut deep. So when I went to Lawrenceville and went to Yale I had a different perspective on the South, and I began to really see the wrongs of segregation. And I talked to a lot of friends, even some of my professors and some of my contemporaries, said that given the wrongs of the segregated system, they just could not go back South again. They had left the South and they were going to spend their lives in the rest of the country. You saw some of that in Willie Morris’ wonderful memoirs called North Toward Home.

.

But for all its flaws, the South was my home. I was gonna go back there because whatever else home is, at least it’s you. I was gonna do what I could to make sure that we saw every citizen as someone worthy of the greatest respect and dignity. I just wasn’t going to abandon my childhood, because along with all the great evil of segregation, I had wonderful parents who cared, raised me with all the caring you could ever imagine. I had friends. I had witnessed many acts of kindness, and my region of the country believed in neighbors helping neighbors, and they believed in strong religious faith, and they believed in country and a man’s duty to serve one’s country, they believed in courage, they believed in truth-telling. So I tried to put my boyhood back in balance. I had lost much in the sense of home, but I also wasn’t about to throw it overboard, because the South, along with its flaws, had many, many virtues. And no person is ever perfect and no region is ever perfect, and it’s this idea you have to keep things in balance.

When I went to Lawrenceville and went to Yale I had a different perspective on the South, and I began to really see the wrongs of segregation.

And so it’s the same way with America. If we can broaden that notion: Many of us have seen the flaws in America, but does that mean we abandon America as our home? No! Just as with my own boyhood, you have to recognize the good along with the bad. And that’s true with America. And there’s so much good along with the mistakes we’ve made. And so when I wrote this, thinking about it, we’re not a sinning nation, and we’re not a sainted nation, but we sure are a nation that’s tried. We have tried to get things right. We have stood for good values across the globe. And we have tried to get things right at home, and we have made great progress in civil rights, and in social welfare and many other nations. So, we have to see ourselves not as a sainted nation, nor as one that only sinned, but as a country that’s tried. We’ve tried.

Ben Weingarten: And, Judge, another section of your book and I think it ties in well to the argument you just put forth, is you say, “The spirit of patriotic sacrifice and universal service is not what it once was. The ’60s saw to that.” How do we rekindle a love of country, and a belief in duty to one’s country in a time when, as you say it today, most Americans are largely removed from war, whereas in the Vietnam era, everyone knew someone essentially who was either being drafted into the war, or conversely, and you describe this in the book, trying to avoid being conscripted into the army.

We're not a sinning nation, and we're not a sainted nation, but we sure are a nation that's tried.

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III: Well, I think a big part of it is trying to recover respect for people who were quite different from ourselves. One thing in the 1960s that upset me a great deal, because it’s also carried over, is that many of the young elites and many of us who were privileged, we looked down on people who were making wonderful contributions to this country. We looked down on the folks who wore the hardhats, and we looked down on people who were in uniform. And we thought that we somehow were making a greater contribution to society than they were, when that’s just not, absolutely not the case. And the earnestness with which the working classes work, and earn a living for their families, and hold down jobs that are important to this country, and the bravery that we saw on the part of first responders, and continue to see in times of emergency…There’s so much reason to respect one another, and it was no reason for what happened in the 1960s, which was to look down on fellow Americans just because they weren’t as affluent as we were, or they didn’t have the education level that we did.

We often look for the bad in other people, instead of looking for the good in our fellow citizens.

And so I try to point out…When I went to basic training, I was guilty of this along with other people because I looked down on this sergeant, and I tell about it in very personal terms. This sergeant who was making me go crawl through one too many sawdust pits, and get up at an ungodly hour, and run until I was ready to drop, and march until I was ready to drop, and I thought he hated me. And then I thought, it’s all come back. And even at the end of basic training, I said, “No. This man did not hate me. He was doing everything he could to save my life.”

And that’s what I’m talking about with these class divisions. We often look for the bad in other people, instead of looking for the good in our fellow citizens. And this class division that was set in motion in the 1960s has carried through in our history. We saw these class divisions emerge in the election of 1972; we saw them emerge in the election of 1980; we’ve seen them emerge in the election of 2016. And they’ve been sown, and they’re not good. And what I worry about is if America at some point faces an existential threat, and we have really got to come together to face it, can we still do it? And I hope so, but I don’t know. And I was saddened by the fact that the camaraderie after 9/11 was so fleeting, and passed so quickly, so I just hope that we haven’t lost the ability to unite if one day, or I should say, when one day, we’re going to absolutely have to.

We looked down on the folks who wore the hardhats, and we looked down on people who were in uniform. And we thought that we somehow were making a greater contribution to society than they were.

Ben Weingarten: My last question was gonna be, “Have the ’60s triumphed?” But I think that you kind of answered that in your final response. I hope, as well as you, that we we can recover some of the core values and principles that have eroded, but it does feel as if we’re fighting a losing battle sometimes.

Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III: Well, it’s important always to hold out hope, because seeing all that’s bad around us should never extinguish hope for what can be good. My feeling is the ’60s inflicted great bad, but they also gave us some good, and how do we preserve the good and recover from the bad. And I don’t think that we can ever lose hope in this wonderful country, because it’s the best country that ever was. And our great leaders, Ronald Reagan, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Lincoln, and Kennedy and Washington, had hope and faith in America. And the very least we owe to them is to carry that hope and faith forward.