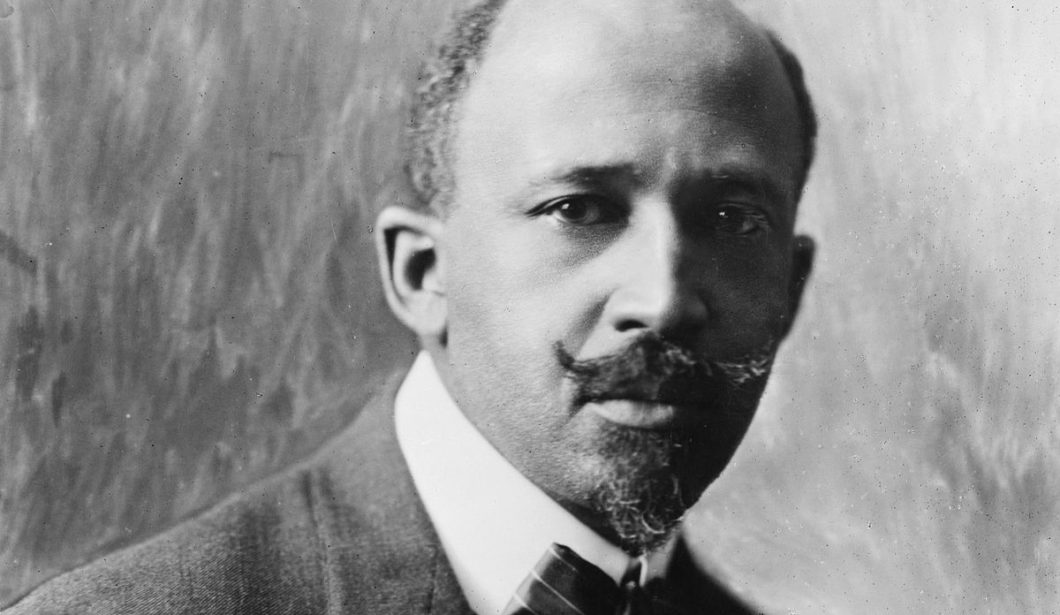

E.WB. Du Bois may have called Reconstruction, the period between 1865 and 1876, “a splendid failure,” but it was a failure nonetheless. This was the time allotted for the adjustment of the slaves to their new freedom. Why was Reconstruction a failure? The facile explanations—lack of political will in the North, President Andrew Johnson’s racial prejudice, and Southern resistance—gloss over the real determinant: Northern and Southern racial attitudes. Until this overriding fact is acknowledged, America will never confront its racial dilemma. Remember, no other group has been asked and encouraged to leave the country by establishment organizations and leaders in both the North and the South. These removal organizations—colonization societies—were founded to send the black population abroad.

.

Following the South’s capitulation, the race-based slavery system that most of the Founding Fathers had hoped would “wither away” was officially dead. Frederick Douglass, the black abolitionist, rhetorically asked, “What shall we do with the Negro?” His famous and oft-quoted answer was “Do nothing. . . . Give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Leave him alone!” Douglass feared that state intervention might raise the specter of blacks as “wards of the state.” He thought that ensuring suffrage, civil rights, general property rights, and an end to discrimination were sufficient protection. Very few Radical Republicans were committed to the extended use of force in reforming the South so as to protect the freedmen. But they did seek a deep government involvement, even land redistribution.

It was never possible that white Northerners would shed white Southern blood for black civil rights. While the story of white Southern resistance is firmly ensconced in history textbooks and heritage events, the critical force of white Northern racial attitudes is a deliberately neglected part of American history. The lame excuses for white Northern apathy during Reconstruction—lack of will and a preoccupation with material concerns—ignores the American consensus about the place of blacks in the society. All the issues of Reconstruction circle back inexorably to the attitude of the white North toward blacks.

“All the issues of Reconstruction circle back inexorably to the attitude of the white North toward blacks”

Despite the North’s dominant position, at the close of the war no firm plan for Reconstruction existed. Political leaders acknowledged the need for a transitional phase for the freedmen, an apprenticeship period or a civilizing status between slavery and freedom. The British post-slavery apprenticeship for its slave colonies thousands of miles away, in the 1830s, was no guide. Moreover, the humanitarian aura of British emancipation was dealt a severe blow when in October 1865 British authorities brutally repressed the bloody Morant Bay, Jamaica, racial insurrection, in which two hundred blacks were murdered. Afterward the British colonial secretary suggested that Jamaicans were “idle, vicious and profligate”; and a British journal thought that the black Jamaican population was moving “back to its ancestral barbarism.” There was no model here for Reconstruction.

The standard story of the postwar years is as follows: The South convinced the North that the Reconstruction governments, in which blacks played a large role, were corrupt and needed to be forcibly removed. Similarly the South successfully created the myth of the “lost cause,” which fostered nostalgia and white reconciliation and minimized the role of slavery as the cause of the conflict. Was the North really this gullible? After all, the North had condescendingly viewed the white Southerner as honor-bound, emotional, indolent, and devoid of commercial skills. It is difficult to imagine that the stereotypical white Southerner could dupe the North. Yet historians claim that white Southerners, a discredited group recently trounced in war, could influence the minds of Northerners.

A more plausible explanation returns to the economic imperatives. For white Americans in the North, the Civil War was a necessary distraction to preserve the Union and abolish race-based slavery. After the war the nation was free to pursue its material goals and populate a continent, both of which had been defining American characteristics from the beginning. The inability of white America to focus on black civil rights cannot be blamed on a sudden attraction to wealth. White Northerners had made an extensive effort to build commercial relations with the South before the war. Northern rails and cities vied for Southern business. Northern economic dominance of the South, some argue, was akin to colonialism.

In the wake of the conflict, King Cotton was a bit shaken but remained on the economic throne. America needed cotton’s export power and fuel for the burgeoning textile industry in the North and subsequently in the South. American cotton would soon provide three-quarters of the world export market for the “indispensable product.” How could America not determine that the future of free blacks was in the cotton fields of the South? The financial system and credit requirements of cotton production did change—to sharecropping, instead of bank borrowing by the landowner. In theory, sharecropping was an arrangement for equity participation by the black farmer; in practice, the black farmer could be easily defrauded because he had no legal recourse. The arrangement was purely arbitrary. Slavery was only the first chapter of the link between African Americans and cotton. Beginning in 1800, slaves cultivated cotton for sixty years, but free blacks were cotton laborers for nearly a hundred years after Emancipation.

.

.

The inability to understand the failure of Reconstruction survives. A New York Times editorial of March 2016 distilled the doom of Reconstruction to two events: “Washington’s decision to no longer enforce the rights of African Americans” and “the rise of the Ku Klux Klan.” But racial attitudes in the white North prevented any sustained federal action to protect free blacks. Even the passage of civil rights legislation and constitutional amendments grew out of the need to keep blacks in the South. Eric Foner’s description of blacks in the North is hardly a paean to racial enlightenment. Northern blacks, according to Foner, were “trapped in urban poverty and confined to inferior housing and menial and unskilled jobs (even here their foothold, challenged by the continuing influx of European immigrants and discrimination by employers and unions alike, became increasingly precarious).” Under such circumstances, blacks had no “viable strategy” for economic progress.

In addition to white Northerners’ dread of a black migration, they feared that former slaves would refuse to work in the cotton fields. Edward Tobey, an influential Bostonian, warned that “If . . . [the freed- men] refuse to work, neither shall they eat.” The abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher declared that “The black man is just like the white . . . he should be left, & obliged to take care of himself & suffer & enjoy, according as he creates the means of either.” Boston anti-slavery advocate Edward Atkinson supplied the militant Kansas abolitionist John Brown with rifles. And he organized the Shaw Monument Fund, which raised money for the Saint-Gaudens statue that honored Robert Gould Shaw, the Boston officer who commanded the black Fifty-Fourth Regiment. But Atkinson agreed that the free black must remain in the South to produce cotton. If not, “Let him starve and exterminate himself if he will, and so remove the negro question . . . ” In 1889 Atkinson was given an honorary degree by the University of South Carolina for his service to the South.

One needs only to read the pages of the New York Times during the late nineteenth century to see why Reconstruction was doomed from the outset. In 1863, in the midst of the war, the Times noted the “vast and most difficult subject of making [freedmen] work” after emancipation. In 1865 the Times wrote that free blacks should be cotton laborers under the supervision of “[w]hite ingenuity.” Further, the Times noted the need to civilize the freedmen over centuries, with some black individuals rising to equality with the white man. In 1883 the Times supported the dismantling of civil rights legislation. And it opposed special rights for blacks who “should be treated on their merits as individuals precisely as other citizens.” In 1874 the Times favored the racial integration of schools in sparsely settled areas of the country where there were few blacks. But in 1890, when a significant number of blacks were involved in a desegregation suit, the newspaper called blacks “foolish” for insisting that their children attend a white school. “Whoever insists upon forcing himself where he is not wanted,” thundered the Times, “is a nuisance, and his offensiveness is not in the least mitigated by the circumstance that he is black.”

“The inability to understand the failure of Reconstruction survives”

Since the Union had not been sundered by the Civil War, and the country saved from the brink of self-destruction, it must have been asked, Who would assist the freedmen? Would their committed, long-term ally be Congress, the president, the Supreme Court, the Republican Party, the white soldiers of the Union Army, white Northern philanthropists, or Northern state governments?

Attitudes produced consequences. White Southern resistance to black equality immediately sought a racial caste system; white Northerners maintained their belief in black inferiority and second-class or, at best, probationary citizenship. Whites North and South in effect helped create a subordinate role for black Americans.

This piece has been adapted from Gene Dattel’s new book, Reckoning with Race: America’s Failure. Original content on EncounterBooks.com is available for syndication. Request permission here.