In Prophetic Statesmanship: Harry Jaffa, Abraham Lincoln, and the Gettysburg Address, Edward J. Erler endeavors to show how the scholarship of Harry Jaffa demonstrated the necessity for a particular kind of statesmanship in a regime dedicated to the principles of natural right—one that might preserve those central ideas by translating them into political action as events and circumstances demand. In attempting to connect political consent of the governed to political reasoning about justice, a statesman engages in an effort that is both essential and uncertain. Erler examines the connections between Lincoln’s most important speeches—the House Divided Speech, his First Inaugural, the Gettysburg Address, and his Second Inaugural—and finds in them the key to understanding America’s significance as a bulwark against reappearing tyranny as well as the triumph and the tragedy of true statesmanship.

—

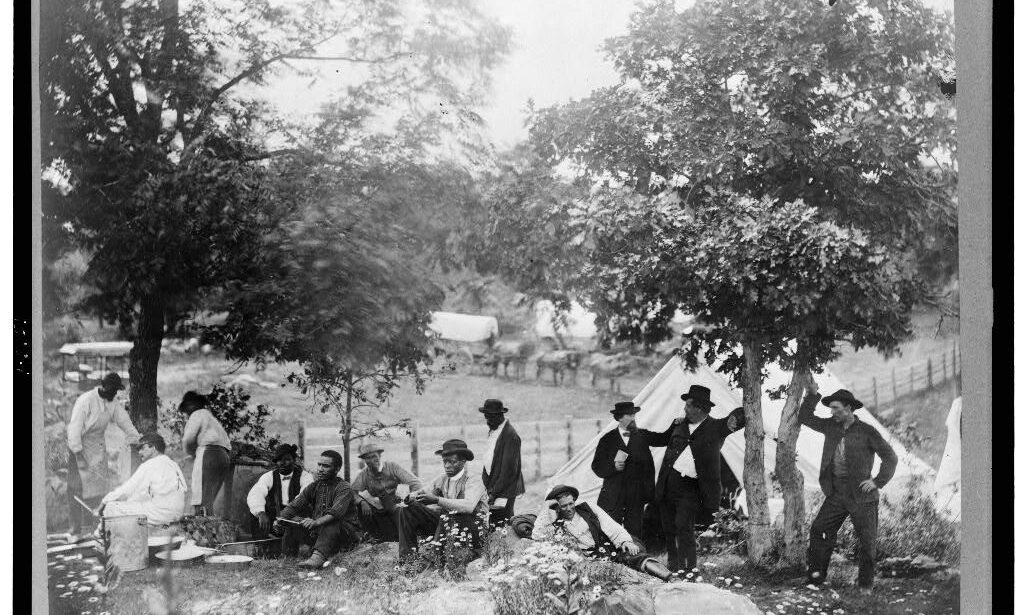

The Civil War was the test of whether a nation “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” “can long endure.” That experiment, which Alexander Hamilton announced in Federalist 1 would “decide the fate of mankind” was still not settled and had reached its ultimate challenge in civil war. The slaveocracy had decided that the experiment had been a failure. The venue of the Gettysburg Address “was a great battle-field of that war.” Lincoln said, “We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that that we should do this.” It is fitting and proper only if those who died on this battlefield did so in a just cause, in the cause of natural right, in the defense of the principles of the Declaration of Independence.

American government was an experiment, and that experiment has not been completed. It was the first attempt in history to establish non-tyrannical government. For Lincoln and the founders, any government that is not based on the consent of the governed is slavery. The American founding presented the question of whether natural right could become political right.

The first sentence of the third paragraph of the Gettysburg Address withdraws the promise of the second paragraph—that it is “fitting and proper” to “dedicate” “a portion” of the field. “But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate. . .” Lincoln now proclaims. How is this a “larger sense?” Lincoln seems to say that the deeds of those who fell in battle have already consecrated the battlefield beyond anything that speech can do. The battlefield has already been consecrated! “My words are not needed,” Lincoln might be saying, “I merely walk in the shade of those who preceded me on the glorious day of their triumph. What he did say is that their deeds were “far above our poor power to add or detract.” Note that Lincoln did not say above “my poor power” but “our poor power.”

The American founding presented the question of whether natural right could become political right...

The next sentence, oft-quoted, is perhaps the most successful example of democratic rhetoric ever voiced: “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.” This is the central sentence of a paragraph that is notable, not only for the absence of the pronoun “I,” but for the frequency of the first-person plural “we.” (Lincoln does not use “I” anywhere in the entire speech). Lincoln, of course, knew that deeds cannot speak for themselves, that unless someone chronicles the deeds—gives them life—they will be forgotten as soon as the eye witnesses themselves are gone. Lincoln knew that his speech—delivered with self-conscious irony—would engender fame and his fame would be reflected upon those who died on the battlefield. He knew that his masterfully crafted rhetoric would bring those who died in the great battle of Gettysburg back to life—resurrected, as it were—so that their lives would live in memory forever. But that would happen only if the nation survives and “shall not perish from the earth.” “It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.” That unfinished work, “the great task remaining before us,” is “that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Thus a “portion of that field” was not dedicated, but “us the living” were “dedicated here to the unfinished work” which those who fought here nobly advanced. The “cause” they advanced was that “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.” Thus, the living will be dedicated, “baptized” as it were, here today for “a new birth of freedom”—a resurrection. Governments can be derived from principles that are eternal, the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God, but at the same time, nations need founders, a philosophic statesman or a phronimos who, knowing what is best by nature, can determine what is best under particular circumstances. The “enlightened statesmen” of the American founding decided to embark on a revolutionary experiment: a regime based on the consent of the governed. That experiment was challenged and in extremis at the time of the Gettysburg Address.

The nation, Lincoln clearly believed, would survive only by a renewal or rebirth of that experiment; but it would require a refounding animated by entirely different motives than those of the founders, motives that are indifferent to—indeed contemptuous of—public recognition. Governments cannot be eternal, but the principles which animate just and free government can be. The Civil War was an effort to preserve “this nation, under God,” but mostly, I say, it was an effort to preserve the principles that make just government possible, that those principles “shall not perish from the earth.” Was it still possible for reason and revelation to be brought together, as they were at the founding, to be the twin pillars upon which the American politeia would continue to rest?

We have already pointed out Lincoln’s opening remarks at his First Inaugural where he characterized his appearance as a “custom” thereby indicating it was not compelled by law. The Second Inaugural is a “second appearing,” which reminds us of the biblical Second Coming, although Lincoln surely would not claim his second appearance to be miraculous. Yet Lincoln’s intention undoubtedly was to remind us of that miraculous event and the necessity of reading the end of the speech in the light of the beginning and the beginning in the light of the end.

Lincoln begins by remarking that this second appearance presents less occasion for an extended address than the first. For the First Inaugural it “seemed fitting and proper” that a detailed account of the course to be pursued should be given. We recall the phrase “fitting and proper” from the Gettysburg Address where Lincoln said it was “altogether fitting and proper” that we “dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that . . . the nation might live.” Thus, Lincoln in the Second Inaugural succeeds in linking together the Gettysburg Address, the First Inaugural, and the Second Inaugural as “altogether fitting and proper.” Fitting and proper, of course, means the speeches were right for the occasions, prudent endeavors to apply the abiding principles of justice to changing circumstances. The Second Inaugural, then, seeks to prepare the American people to receive God’s justice for the sin of slavery.

Read more in Prophetic Statesmanship: Harry Jaffa, Abraham Lincoln, and the Gettysburg Address