Six years after the founding of National Review, a philosophical chasm suddenly formed between close friends and fellow senior editors Frank Meyer and L. Brent Bozell. In 1960, Bozell ghostwrote Barry Goldwater’s Conscience of a Conservative and migrated to Francisco Franco’s Spain. By early 1962, he had veered sharply from the pro-freedom conservatism for which he previously shared an enthusiasm with Meyer and Goldwater. What happened? Spain happened. As Bozell tried to coax Meyer there, Meyer attempted to rescue Bozell from foreign ideas and their friendship from threats from this newfound tension. The ongoing debate furthered not the fusion that Meyer so wanted for conservatives but a fissure that gave identity to emergent strains of conservatism. Unlike almost every other conversation in the history of the postwar right, this one continues unabated and with far more debating partners in 2025 than in 1962.

—

“Both of us consider the evening on Ohayo Mountain one of the high spots of our year,” L. Brent Bozell wrote on behalf of his wife in the fall of 1956. He returned frequently to talk the night away. More frequently did he find other ways to engage his conversation partner.

“My genius is distinctly for the telephone rather than the epistolary,” Meyer later confessed in a letter to Bozell. He knew himself.

Initially, the devices were black, mounted, and rotary. They miraculously transmitted an isolated man’s voice to fellow conservatives. They also sent out a massive portion of his income. Bozell siphoned the largest part of his phone bill in these years.

“A running joke at NR was Willmoore Kendall’s quip that an emergency phone call between Frank Meyer and Brent Bozell was a call that interrupted their usual call,” Priscilla Buckley wrote. “Frank Meyer was AT&T’s best customer.”

The calls came unexpectedly and often during sleeping hours. Their frequency led Bozell and Meyer, witnessed by Marvin Liebman, to draw up a contract of sorts ridiculing the situation:

Brent Bozell, the party of the first part (Natch!), and Frank S. Meyer, the party of the second part, have conferred on various matters unpleasant to relate, and have reached the following understanding:

1. That the party of the second part has thoroughly & profligately dissipated funds entrusted to him & others by incessant & interminable phone calls to no purpose;

2. That the party of the second part sincerely regrets the abuse of the authority bestowed on him by the party of the first part (i.e., the permission to use telephone);

3. That the party of the first part forgives;

4. That the party of the second part undertakes & pledges to party of first part and to one M. Liebman that any & all phone calls made by party of second part from now until 27th day of Sept, 1959 will be personally paid for by party of second part as justice and penance doth require.

Subscribed to this 16th day of September 1959

Brent Bozell

Frank S. Meyer.

One could afford Ivy League tuition, room, and board and still go on a $1,000 spending spree with the money Meyer spent on long-distance charges. The year the two friends crafted their contract, the Meyers spent $3,417 on telephone bills. This amounted to 58 percent of the salary he drew from the magazine and 30 percent of his taxable income. The following year, the phone bills they wrote off calculated to 56 percent of his National Review income, which had ballooned by about $1,000 to $7,000. Along with a lit cigarette, the telephone symbolized Frank Meyer.

The phone allowed him to influence affairs at National Review. The magazine directed other inner-directed men elsewhere. Meyer avoided defenestration not by any conscious act but by rarely venturing into the office and not so much as even keeping a desk there. This disadvantaged him in pushing the editorial line. It also determined that Meyer, if frequently quarreling with [James] Burnham or occasionally annoying [William F.] Buckley, never wore out his welcome. One could generally choose to deal with him or not.

Arlene Croce, one of the editors tasked with putting issues to bed, recounted, “Frank was a telephone person to me always.” Neal Freeman explained, “I used to joke to the Meyer boys that AT&T invented caller ID to solve the Frank Meyer problem. He would call at two in the morning knowing you would be home, but you didn’t know whether it was the widow next door or if your parent might be in trouble. So you would pick it up. And, of course, it would be Frank, and you had to catch the 6:45 train in the morning. You were not eager to speak to Frank all of the time.”

Bozell and Meyer eagerly communicated with one another all of the time. With Bozell in Spain, mail replaced telephone and another agreement—committing recipient to respond to sender within seventy-two hours—governed correspondence. Occasionally, they communicated in the magazine’s pages before a paying audience.

Meyer’s first National Review article of 1962 read as unlikely fuel for an explosive debate whose residue coated articles, conference panels, and books for decades.

“The Twisted Tree of Liberty,” which ran as a standard article rather than under “Principles and Heresies,” started out as taxonomy of conservatus americanus detailing the characteristics of the myriad genera of the growing family. Meyer noted that some strains veered so far from the family tree in emphasizing an aspect of conservatism that they wound up in opposition to it. His anti-Communism overwhelmed his libertarianism in excommunicating a subset of libertarians who advocated disarmament and pacifism in response to Soviet aggression. He privately characterized them as “treasonous characters” to Bozell.

Bozell regarded it as clever that a libertarian defended traditionalism from fringe libertarianism in a way that not only did not dismantle some aspect of libertarianism but elevated it to conservative orthodoxy. He playfully vowed revenge.

“I am hard at work on an article reading you out of the conservative movement—and you wouldn’t want to interrupt that, would you?” he offered as an excuse to a violation of their seventy-two-hour pact. “Which is to say, son, when you finally get the ‘opportunity to meet [my] arguments,’ you will have them in front of you in NR in a piece that will have created, unless it is laughed at, the biggest stink the movement has smelt in some time. This assumes, of course, it will be published. If it’s not, I will have to resign. It’s one of the things I will want to talk to you about since I am not above us arranging to have it published in Bill’s absence. In general, it is an attack on freedom. Fritz [Wilhelmsen], you will be happy to know, and God, agree with me.”

That month, a similar sharpening of the meaning of postwar conservatism occurred in the magazine’s pages when Morton Auerbach repeated his claims that the postwar right lacked coherence and overflowed with contradictions. Meyer, M. Stanton Evans, and—most effectively—Russell Kirk rebutted the liberal professor. The exchange displayed the degree to which the magazine of opinion operated, contra the wishes of Burnham (a former professor of philosophy at New York University), as a journal of political philosophy.

... Morton Auerbach repeated his claims that the postwar right lacked coherence and overflowed with contradictions. Meyer, M. Stanton Evans, and—most effectively—Russell Kirk rebutted the liberal professor.

On that side of the Atlantic, crises beyond philosophical disagreement called for the Meyers to come. L. Brent Bozell endured deep depressions, and the alcoholism of his wife required care from the psychiatrist Juan José López-Ibor, under whose spell both Bozells, [Willmoore] Kendall, and Virginia Wilhelmsen all fell. Returning to America, a scenario Meyer strenuously argued for, Brent insisted, might mean institutionalization for Tish, a scenario Meyer strenuously argued against. They all hoped for a Spanish visit from the Meyers. Problems associated with the Newark building rented out to a Schrafft’s restaurant, his aunt’s failing health, book deadlines, pending college tuition, Volker money drying up, and Elsie’s recent struggles with pleurisy, pneumonia, and gall bladder surgery conspired to ensure that the three amigos never reunited in Spain, a place that a quarter century before had claimed the life of one Meyer confidant and here taxed friendship with others.

Bozell and Meyer settled on a two-day meeting of the minds. “We are looking forward, like children to Christmas, to your arrival,” Meyer wrote in February. Though 3,500 miles apart, the couples remained close. Bozell, around the time of their meeting, successfully pushed Buckley to give Meyer a raise. Meyer lobbied Buckley to publish the article rebutting himself and talked about it with the Circle Bastiat member Ronald Hamowy, who offered to run it in The New Individualist Review, an option as appealing to Bozell as New Masses printing one of his articles.

“The main point is that the farthest thing from my mind was to give any impression that our personal friendship is in any way affected,” Meyer clarified following a transatlantic phone conversation. “After all, we have said much more violent things privately than we are ever going to say in print.”

That the odd Meyer piece reproving libertarians catalyzed Bozell to launch a six-thousand-word fusillade and do so eight months later said as much about the critic as it did the criticized. The critic heartily agreed with the article’s main point anathematizing the libertarians who were countering Soviet belligerence with demilitarization. Bozell, an American Legion national oratory champion in high school and anchor of a Yale debate team whose victory over Oxford undergraduates left the stunned Brits refusing to shake hands, relished intellectual combat. “The Twisted Tree of Liberty” extended an olive branch; Bozell snatched it to pummel the opponent. Meyer, himself also of that rare breed of human beings to develop a carapace, if only operational during intellectual disagreements, appreciated in Bozell what alienated others from both. They happily went at it, grateful to the other for sharpening their arguments.

Whereas Meyer stressed common denominators of traditionalism and libertarianism, Bozell emphasized difference to the point of irreconcilability. Indeed, the articulated positions exhibited a gap between them in the power each entrusted to the state. One gifted it enormous dominion; the other jealously restrained it.

In “Freedom or Virtue,” Bozell pegged man’s goal as virtue and politics as a means to aid in this pursuit. Freedom for freedom’s sake, he reasoned, represented a rebellion against God and nature.

“If the link between economic and other freedoms is thus tenuous, and if freedom, in any event, is difficult to translate into a ‘transcendent value,’ the real reason libertarians assign absolute value to economic freedom probably lies elsewhere,” he reasoned in perhaps the article’s most penetrating section. “And I suspect that the explanation is as simple—and as ominous for the future of conservatism—as a group hangover from the century when the argument about the interdependency of freedoms was exactly reversed: when, that is to say, instead of demanding economic freedom for the sake of political and other freedoms, libertarians demanded the other freedoms for the sake of economic freedom.”

Profound insights into the libertarian mind came from a libertarian mind in recovery. He now saw a model of the good state in Francisco Franco’s Spain. Bozell, if nothing else, was a seeker. His debating partner clearly, if not to himself, journeyed, too.

The article’s rhetorical flashes, more so even than its gobbling up more than seven full pages in the magazine, arrested readers. Bozell ridiculed Meyer’s three natural functions of government—order, justice, defense—as “the mystery of the trinitarian state” and translated the line that “virtue-not-freely-chosen is not virtue at all” as “leading inescapably to the burlesque of reason.”

Atop the philosophical depth and literary talents displayed, the author prophetically analyzed liberalism, despite an illusory Camelot in the White House, as a spent intellectual force awaiting political collapse. What filled the void?

Bozell cited efforts of Meyer and Evans (and invoked YAF’s Sharon Statement, influenced by the former and written by the latter), and goals as modest as consolidating the right to as ambitious as capturing the government. Devoted readers, unaware of developments on the Iberian Peninsula, undoubtedly had regarded this Meyer–Evans project as a Bozell–Meyer–Evans project. Bozell’s pivot announced that Meyer’s cause, ostensibly to define conservatism and unite its disparate strands, faced opposition. Tracing that call to if not inside the house than at least to the caller so frequently on the line accentuated the effort’s difficulty. If Meyer could not convince—and given Bozell’s conversion from essentially a Meyerite position to one more extreme than Kirk’s—the man visiting his home, invading his mailbox, and tying up his telephone line, how could he expect to persuade millions of strangers?

Atop the philosophical depth and literary talents displayed, [Bozell] prophetically analyzed liberalism, despite an illusory Camelot in the White House, as a spent intellectual force awaiting political collapse.

Two weeks later, Bozell’s friend and fellow senior editor responded. He noted that YAF, ISI, and, probably as an inside joke, The Conscience of a Conservative all took his side. He now did not seek to invent conservatism but merely to articulate it.

“Why Freedom” described a project “very different from an ideological—and eclectic—effort to create a position abstractly ‘fusing’ two other positions. What I have been attempting to do is to help articulate in theoretical and practical terms the instinctive consensus of the contemporary American conservative movement—a movement which is inspired by no ideological construct, but by devotion to the fundamental understanding of the men who made Western civilization and the American republic.”

What appeared in National Review in 1962 differed greatly from what appeared in The Freeman in 1955. This iteration of Meyer moved away from the lingering Communist mindset that reflexively offered a system toward a conservative mindset that noted the prolonged development of tried and tested ideas. Now he depicted his political philosophy as an acknowledgement of the best that made the West rather than a system conveniently concocted for political purposes. Bozell assumed the role of the gadfly Meyer of 1955 and Meyer played, poorly, the bothered horse Kirk.

Meyer stressed that fusionism derived from the tradition of Western civilization and the American Constitution. His three-page article conveyed that freedom amounted to the tradition of the West but that the West’s tradition stewarded “virtue in freedom.” The former required the latter to express itself; the latter required the former to imbue meaning.

Fidelity to one to the extent that it dismissed the other necessarily ran contrary to conservatism. “Why Freedom” explained that “the rigid positions of doctrinaire traditionalists and doctrinaire libertarians were both distortions of the same fundamental tradition and could be reconciled and assimilated in the central consensus of American conservatism.”

Bozell’s heretofore closest sounding board advocated a political philosophy profoundly different than any developed in Spain. Meyer defended a conservatism of the American Founding against a conservatism of the fruit of foreign soil.

“The denial of the claims of virtue leads not to conservatism,” he explained, “but to spiritual aridity and social anarchy; and the denial of the claims of freedom leads not to conservatism, but to authoritarianism and theocracy.”

Not everyone agreed.

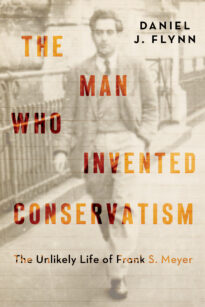

Read more in The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer