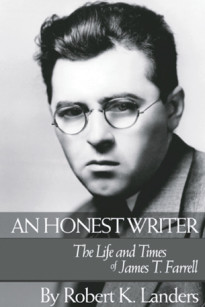

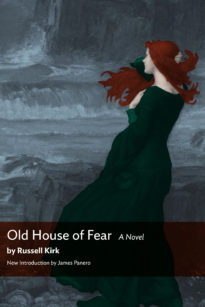

A founding father of the American conservative movement, Russell Kirk (1918–94) was also a renowned and bestselling writer of fiction. Kirk’s focus was the ghost story, or “ghostly tale” – a “decayed art” of which he considered himself a “last remaining master.” Old House of Fear, Kirk’s first novel, revealed this mastery at work. Its 1961 publication was a sensation, outselling all of Kirk’s other books combined, including The Conservative Mind, his iconic study of American conservative thought. A native of Michigan, Kirk set Old House of Fear in the haunted isles of the Outer Hebrides, drawing on his time in Scotland as the first American to earn a doctorate of letters from the University of St. Andrews. The story concerns Hugh Logan, an attorney sent by an aging American industrialist to Carnglass to purchase his ancestral island and its castle called the Old House of Fear. On the island, Logan meets Mary MacAskival, a red-haired ingénue and love interest, and the two face off against Dr. Edmund Jackman, a mystic who has the island under his own mysterious control. This new edition features an introduction by James Panero, Executive Editor of The New Criterion.

Free shipping on all orders over $40

Old House of Fear

Also Purchase as e-Book

Publication Details

Paperback / 264 pages

ISBN: 9780985905286

Available: 10/29/2019

- Media: Request a Review Copy

- Academia: Request an Exam Copy

About the Author

Russell Kirk was the apostle of “permanent things.” His book The Conservative Mind, published in 1953, was the rallying point for the renewal of a long-dormant spirit of serious attention to the founding moral, religious, social, and political principles animating the ideal of ordered liberty, especially in its flowering in the grand American experiment in self-governance.

Praise

Excerpt

On this shrouded night, five men tossed in a boat off

the island of Carnglass, where the sea never is smooth. So

thick about them hung the fog that they could not see the

great cliffs. Knowing, though, every rock and reef, they

sensed where the island lay.

Of a sudden, a tall flame shot up from Carnglass, fierce

and unnatural. Across the swell there came to the men in

the boat the crash of some explosion. Clinging to their oars,

they stared silent toward the land; the oldest man crossed

himself. The flame, surging and waving for some minutes,

soon sank lower. In a little while they heard faint distant

sounds, several of them, like gunshots. The younger men

looked to the old helmsman, who pulled hesitantly at his

white beard.

Then he signed to them to put the boat about. Glancing

fearfully at the distant flame as they heaved, two men

hauled at the sail. In a minute they had changed course, and

the fire in the night glowed at their backs as they pulled

away from the uneasy neighborhood of silent and invisible

Carnglass.

Three thousand miles away, two men sat in a handsome office.

“That’s our island,” Duncan MacAskival said: “Carnglass.”

Across the Ordnance Survey map his thick forefinger

moved to a ragged and twisted little outline, away at the

verge of the Hebrides, which even upon the linen of the map

seemed to recoil from the Atlantic combers. “The tattered

top of a drowned mountain. And that’s the castle, by the bay

to the West, Hugh: Old House of Fear. I like the names.

You’re to buy Carnglass for me, cliffs and clachans and deerforest

and Old House and all; and price is no object.”

Hugh Logan smiled at the heavy old man in the swivel

chair. “Why send me to the Western Isles to haggle for a

speck of rock I know nothing about, Mr. MacAskival? Why

do you need Carnglass? And why not have a Glasgow solicitor

do the business for you? I’d enjoy the trip, right enough,

but I don’t need to tell you that my time costs you bona fide

money. Any junior clerk could buy an island for you.”

“Look out there, Hugh.” MacAskival swung round his

chair to the big window at the back of his teak-panelled

office. Far below, stretching eastward for a quarter of a mile

along the river, the stacks and coke-ovens and corrugatediron

roofs of MacAskival Iron Works sent up to heaven their

smoke and flame and thunder. “Look at it all. I made it. And

what has it given me? Two coronary fits. I’m told to rest. But

where could a man like me fade decently? I’m not made for

quiet desperation. There’s just one place, Hugh, where I

might lie quiet; and that’s Carnglass.”

MacAskival peered at his map. “I haven’t seen Carnglass,”

he went on, “except in pictures, and no more did my father,

or his father. But the MacAskivals came out of Carnglass to

Nova Scotia in 1780, and they didn’t forget the little croft

below Cailleach – that’s the sharp hill north of the Old

House, Hugh. Their Nova Scotia farm was sand and stumps,

and yet not so barren as that Carnglass croft. Still, they’d

have traded ten farms in Nova Scotia for that wet little plot

in Carnglass. And after two strokes, I think I’d give the mills

and all for that croft – with the island thrown in.”

Logan had walked to the window, and now stood looking

toward the glare of the coke-ovens; the flames went up

hotly into the Michigan twilight, that April evening, and

the incandescent masses of coal fell roaring. “Why, I think

we might make a better bargain than that, Mr. MacAskival.

Peat bogs and tumbledown castles go cheap nowadays. But

why do you mean to send a man like me to buy you a few

square miles of dripping misery?”

“Cigar, Hugh?” MacAskival pushed a box toward him.

“The doctor says I can have just one of these a day. Well, I’m

not so crazy as I seem, and you know it. Under your veneer,

you’re like me – sentimental as a sick old ironmaster. Don’t

tell me you’ve never thought of having an island all to yourself.

So I’d like to see you hunt this dream of mine; you work

too hard for your age. ‘Getting and spending, we lay waste

our powers.’ I don’t plan to bare my bosom to the moon in

Carnglass, but it should do you good to play at being a

pagan suckled in a creed outworn – for a few days, anyhow.”

Old Duncan MacAskival was a trifle vain of his quotations

and allusions, Logan thought. But Logan liked MacAskival,

a self-made man, a good deal better than the average

product of the big business-administration schools. It came

to Logan that he, Hugh Logan, rapidly was growing into an

old man’s young man. It had been more than a dozen years

since he had led a battalion in Okinawa. He knew much of

Scotland, born in Edinburgh as he had been, though his

parents had taken him to America when he was nine; and he

had gone back to take a degree at Edinburgh University. A

slackening of pace, for a week or two, might do no mischief.

All his life he had hurried: schools, the university, the war,

and the firm: in too much of a hurry, either side of the water,

to laugh, to marry, or even to dream. “No Mr. MacAskival,”

Logan said, “I’m not the man to laugh at you. But you’re a

canny Scot, though five generations removed. Do you need

to pay my price just to draw up a deed to an island?”

“You’re more of a Scot than I am, Hugh, though you look

American enough nowadays.” MacAskival leant back in his

heavy chair. “Well, yes, you’ll be worth your price in this

business. You know something of Scots law and tenures. And

you can wheedle odd customers; Lady MacAskival is one of

that breed, they tell me. Here, look at yourself in that mirror.”

MacAskival nodded toward the baroque glass against

the teak panelling.

Logan saw reflected a mild-seeming, amiable face – or so

most people would call it, probably – almost unlined; still a

young man’s face. Sometimes, when he had been a major of

infantry, that face had tended to mislead people, and then

Logan had to rectify impressions. He had a spare body. “Do

I look like a fool?” he asked MacAskival.

“Not exactly a fool, boy, but close enough. You’re innocent:

that’s the word, Hugh. What a face to set before a jury –

or a crazy old creature like Lady MacAskival! Anyone signing

a contract with you assumes that he’s had the better of the

bargain. Now I’ve tried before this to buy Carnglass; I’ve been

at it more than three years. I’ve tried those Glasgow solicitors.

They’re too sharp: what we need with Lady MacAskival

is babyish innocence.”

“Can’t you find any intermediary but a Glasgow solicitor?”

“Why, Hugh, somehow I got in touch with a retired major

or captain – Indian Army, I think – who wrote that he might

do my business for me. He seemed to want his palm greased.

His name was George Hare, or George Mare, or something

of that sort.”

Logan rubbed his chin. “In Glasgow? There was a criminal

case, if I’m not mistaken – something to do with state

secrets, or vexing little girls, or some nasty affair – in Scotland,

a year or two ago, with the defendant a cashiered Indian

Army officer – and that sort of name. I may have a clipping

about it in my files. I’m not sure, though, that the name was

either Hare or Mare. A captain, I think.”

“For all I know, Hugh, this may be your man: anyway,

though I greased his palm in moderation, I’ve never had a

line from him since. He said he knew Lady MacAskival. So

that’s a bribe down the drain. Now will you take my shilling?”

“All right: I’ll take my innocence to Carnglass.” Smiling,

Logan turned back to the map on the big desk. “There still

are MacAskivals in the island, then? And what sort of cousin

of yours is this Lady MacAskival?”

“Call me Duncan, Hugh,” MacAskival said, “if you’ll really

take up the business for me. No, there’s not a real MacAskival

left in Carnglass, so far as I can learn. Lady MacAskival was

born Miss Ann Robertson; her family owned distilleries,

money-makers. It was a queer match when she married Colonel

Sir Alastair MacAskival, Indian Army, who was old

enough to be her father, or more. Sir Alastair had scars and

medals, but nothing besides. Though he was chief of the MacAskivals

– and there’s precious few of that little clan left – he

was born in a but-and-ben in North Uist. I get all this from

an Edinburgh genealogist. Sir Alastair’s great-grandfather

ran through his property so as to keep up a fine show in

London. The Great Clearance of Carnglass was in 1780 –

that’s when my people were booted out, you remember –

and it was the work of that old reprobate Donald MacAskival,

our Sir Alastair’s great-grandfather: he turned the whole

island into two big farms and a sheepwalk, on the chance of

squeezing more money from the rents, and told all the crofting

MacAskivals to go to Hell or Glasgow. A few had the

money for steerage passage to Nova Scotia, which eventually

made me president of MacAskival Iron Works. My father

was a pushing Scot, and so am I – and you, too, Hugh.”

“So Ann Robertson brought money back to the MacAskivals

more than a hundred years after the Clearance?”

“Not simply money, Hugh, but Carnglass itself. What

little extra Donald MacAskival contrived to wring out of the

rents after the Great Clearance did him no good. He died

bankrupt; and the creditors took Carnglass. His son sank

down to being the factor for a small laird in North Uist, and

there the family lived on, hand to mouth, until young

Alastair went out to India and got some reputation for himself

along the Northwest Frontier. When he was past forty,

he sailed home to Edinburgh on leave. There he met Ann

Robertson, and married her, and they bought back Carnglass

with Robertson money, and restored Old House of Fear.